Verrrry interesting new supercar concept to share! Meet the 2015 Divergent Microfactories Blade.

Verrrry interesting new supercar concept to share! Meet the 2015 Divergent Microfactories Blade.

The product of a Palo Alto-based tech startup, the Blade highlights the rapidly falling barriers to entering the automotive business. One-time giant fixed costs like factories and industrial presses are on the outs thanks to innovations in material science.

While billed by many as the 3D-printed supercar, that does not strictly seem to be the case. Yes, many components in the Blade are produced in an unconventional fashion — but are the truly 3D printed pieces on display, or mostly hidden details?

The main chassis evolves from a tubular racecar frame method, but replaces steel or high-strength alloys for carbon-fiber in the tubes. These carbon-fiber tubes can be produced on a standardized fashion, joined by a proprietary ‘Node’ of aluminum connector piece.

Once bonded and stiff as a board, the resulting chassis weighs just 120 pounds as the sole structural element of the car. Like the Corvette for seven decades, a stiff frame below lets the panels relax as unstressed members of the vehicle. Not a unibody, then, where the metal fenders of a Honda Civic, etc, are part of the overall structure of stamped metal panels below.

CORVETTE ASSEMBLY METHODS COMPARISON

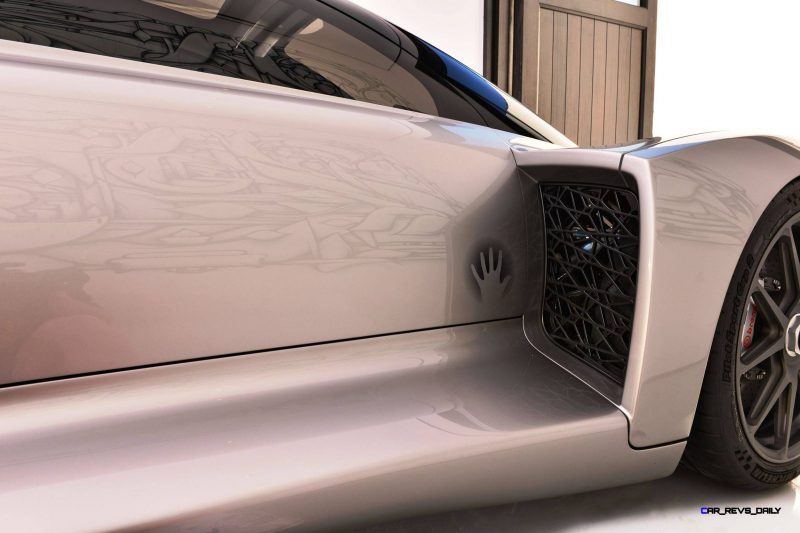

The Blade uses a variety of CFRP polymers for its wild and sci-fi bodywork. The Blade’s design is gorgeous and exceptionally unique. The in-board passenger compartment and scissor doors provide natural wings, scoops and aero that feel at home with the latest hypercar crop from Pagani and Ferrari. The front fender vents are giant rectangles of mesh area that are seriously cool and sexy.

Seating the driver and passenger in tandem, the ultra slim cockpit recalls the Lambo Egoista and a few Vision Gran Turismo prototypes for single seaters. While the back seat will not be hugely roomy, it is great to find it there in general. We initially thought it was a single-seater — which is cool but not as fun as sharing the ride with a pal. Additionally, the seat arrangement might make the Blade a quad-bike by federal standards — and therefore road legal sans airbags etc. More on this below.

LED headlamps from the Cadillac Escalade and a tuned Lancer Evo engine are just two of the recycled component sets in the Blade. The performance and exceptionally low weight are both approximates at this time — but are impressive nonetheless. 1400-pounds and a sprint to 60-mph of 2.0-seconds are slightly dubious, as is the 700HP output of the Evo’s 2.0-liter four-cylinder. Running either natural gas or gasoline, the four-cylinder is mid-mounted with giant air scoops all around to feed its turbo intercooler and intakes.

ANALYSIS

As the first concept from DM, it is not instantly clear if the company is selling its ideas and intellectual property as a supplier/manufacturing partner to OEMs, or if this car is actually the product to be sold to consumers.

Divergent helps clarify this in their convincing business case/whitepaper below — where they describe the goal of producing the Blade for sale to a limited number of buyers.

We’d ballpark a price of $550,000 to order one today.

The overall benefits of the low-volume exotic materials do seem to be a perfect match for the hypercar business — where newness and rarity are just as important as outright performance or brand legacies.

With a Corvette-like assembly process of bodywork lowered atop a complete chassis/frame below, in theory Divergent could swap out the design to a different one easily. This could be annual product refreshes, bespoke elements for a roadster, or a totally different type of ‘topskin.’

One issue we’d like to see addressed, however, is the actual labor of assembling the vehicle. Many of the benefits of traditional industrial manufacturing is that it can achieve sky-high volume and be extensively automated. On the contrary, Divergent (at first) will be hand-assembling these from start to finish.

The second is the viability of CFRP panels. TVR loved these types of molded panels for their fiberglass bodywork — with the molds almost all that is left at their Blackpool HQ these days.

It is not immediately clear that these are actually 3D-printed, versus ordered from a giant factory somewhere far, far away. Ordering out would make big scale viable — printing in Palo Alto would, by contrast, drastically limit overall volume. Panels this size might take days or weeks to actually print from nothing — via thousands of mini layers of polymers. Think of it like printing a 200,000-page document to a clunky Epson inkjet. It would take a while to complete.

But overall, the Divergent Microfactories BLADE is a very promising development in the supercar business. Bringing startup ingenuity of Silicon Valley — plus VC investors nearby who are frequent supercar owners — to the small-batch supercar game seems like a very exciting development for the industry as a whole.

The production values and design quality of the Blade prototype definitely seem up to the task of challenging supercar legends. Just look at the gorgeously avant-garde mesh for the air intakes, the center-lock alloys and the clear-cased spike of brake light elements. Or look at the incredibly sexy details of the fuselage canopy and well-resolved aero detailing.

If the Blade’s performance and road legality questions can be resolved, the Blade might be just the first of a new range of infinitely customizable exotic cars.

2015 Divergent Microfactories BLADE Concept

2015 Divergent BLADE Concept

Divergent Microfactories Drives the Future of Car Manufacturing with Blade:

World’s first 3D-Printed Supercar Built Using Company’s ‘Node’ Technology Platform

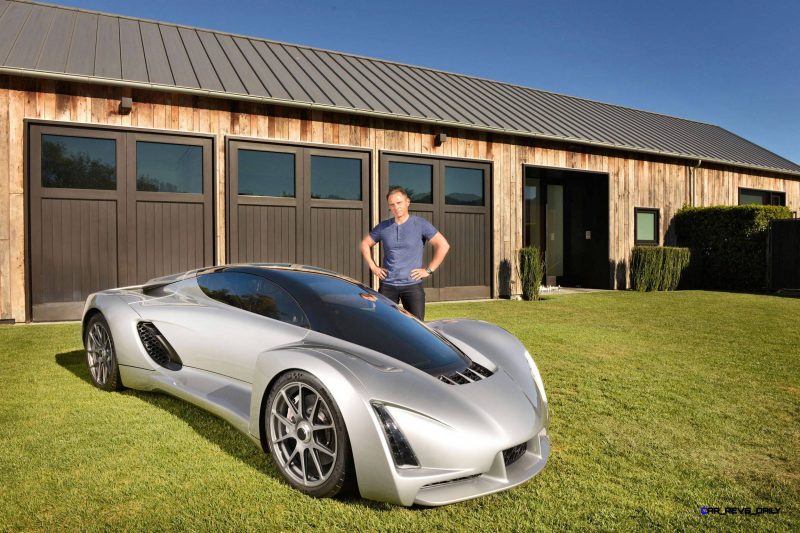

SAN FRANCISCO, Calif – June 24, 2015 – Divergent Microfactories today unveiled a disruptive new approach to auto manufacturing that incorporates 3D printing to dramatically reduce the pollution, materials and capital costs associated with building automobiles and other large complex structures. Highlighted by Blade, the first prototype supercar based on this new technology, Divergent Microfactories CEO Kevin Czinger introduced the company’s plan to dematerialize and democratize car manufacturing.

“Society has made great strides in its awareness and adoption of cleaner and greener cars. The problem is that while these cars do now exist, the actual manufacturing of them is anything but environmentally friendly,” said Kevin Czinger, founder & CEO, Divergent Microfactories. “At Divergent Microfactories, we’ve found a way to make automobiles that holds the promise of radically reducing the resource use and pollution generated by manufacturing. It also holds the promise of making large-scale car manufacturing affordable for small teams of innovators. And as Blade proves, we’ve done it without sacrificing style or substance. We’ve developed a sustainable path forward for the car industry that we believe will result in a renaissance in car manufacturing, with innovative, eco-friendly cars like Blade being designed and built in microfactories around the world.”

Divergent Microfactories’ technology centers around its proprietary solution called a Node: a 3D-printed aluminum joint that connects pieces of carbon fiber tubing to make up the car’s chassis. The Node solves the problem of time and space by cutting down on the actual amount of 3D printing required to build the chassis and can be assembled in just minutes. In addition to dramatically reducing materials and energy use, the weight of the Node-enabled chassis is up to 90% lighter than traditional cars, despite being much stronger and more durable. This results in better fuel economy and less wear on roads.

The centerpiece of the Divergent Microfactories announcement is Blade, the world’s first 3D-printed supercar. Designed and built using Divergent Microfactories’ technology, the prototype is one of the greenest and most powerful cars in the world. Equipped with a 700-horsepower bi-fuel engine that can use either compressed natural gas or gasoline, Blade goes from 0-60 in about two seconds and weighs around 1,400 pounds. Divergent Microfactories plans to sell a limited number of high-performance vehicles that will be manufactured in its own microfactory.

In addition to unveiling its technology platform and prototype, Divergent Microfactories announced plans to democratize auto manufacturing. The goal is to put the platform in the hands of small entrepreneurial teams around the world, allowing them to set up their own microfactories and build their own cars and, eventually, other large complex structures. These microfactories will make innovation affordable while reducing the health and environmental impacts of traditional manufacturing.

For more information on Divergent Microfactories, visit www.divergentmicrofactories.com.

Divergent Microfactories Social Media:

Twitter: @DMicrofactories

Facebook: http://on.fb.me/1FMeYMo

LinkedIn: http://linkd.in/1GAzrcP

Kevin Czinger Social Media:

Twitter: @CzingerKevin

LinkedIn: http://linkd.in/1Mu1KI0

About Divergent Microfactories:

Divergent Microfactories is dedicated to revolutionizing car manufacturing and its harmful health and environmental impacts on the planet. Led by Founder & CEO Kevin Czinger, Divergent Microfactories has created a manufacturing platform that radically reduces the materials, energy, and costs of manufacturing. Divergent Microfactories aims to put these new tools of production and innovation into the hands of small teams all around the world, resulting in a sustainable path forward for the car industry and beyond. For more information, visit www.divergentmicrofactories.com.

DIVERGENT MICROFACTORIES

WHITE PAPER

Dematerialization and Democratization in Auto Manufacturing

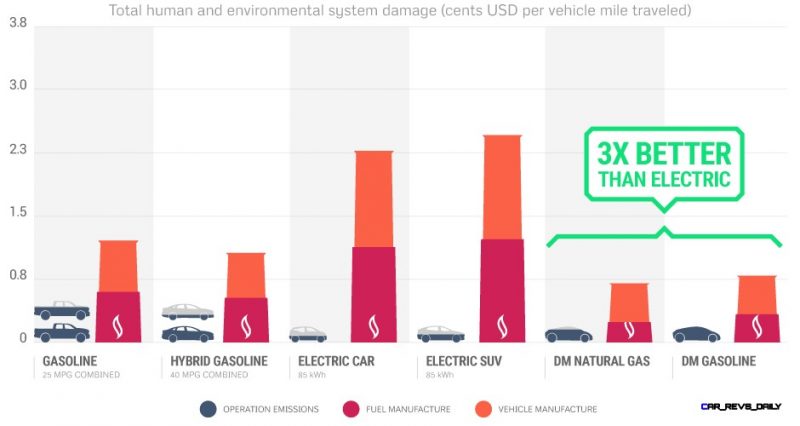

Around 2 billion cars have been built over the last 115 years; twice that number will be built over the next 35-40 years.[1] The environmental and health impacts will be enormous. Some think the solution is at hand with electric cars or other low or zero emission vehicles. The truth is that if you look at the emissions of a car over its total life, you quickly discover that tailpipe emissions are just the tip of the iceberg. An 85 kWh electric SUV may not have a tailpipe, but it has an enormous impact on our environment and health. A far greater percentage of a car’s total emissions come from the materials and energy required for manufacturing a car—the mining, processing, manufacturing, and disposal of the car itself, not the car’s operation. As leading environmental economist and Vice Chair of the National Academy of Sciences Maureen Cropper notes, “Whether we are talking about a conventional gasoline-powered automobile, an electric vehicle, or a hybrid, most of the damages are actually coming from stages other than just the driving of the vehicle.”[2] If business continues as usual, we stand to increase the total global pollution generated by automobiles by three times or more, as we go from 2 billion to 6 billion vehicles manufactured. The conclusion from this is straightforward: how we make our cars is actually a bigger environmental issue than how we fuel our cars. We need to dematerialize—to dramatically reduce the material and energy required to build cars—and we need to do it now.

These facts are demonstrated in a 2009 report by the National Academy of Science, Hidden Costs of Energy: Unpriced Consequences of Energy Production and Use. That report considers the total human and environmental damage stemming from the various stages of automotive use: the manufacture of the vehicle, the manufacture of the vehicle’s fuel, and the operation of the vehicle. This chart makes clear that tailpipe emissions are only a small part of the total emissions picture:

Thus, the prevailing marketing and policy focus on drivetrains (e.g. gasoline vs. electric) has dangerously obscured the debate and drawn our attention from the larger problem: the emissions and other environmental damage stemming from the manufacturing of cars.

We therefore need to focus our innovation not simply on automobile products, but at least as much on the process by which those products are made. Such process innovation needs to accomplish two equally important goals:

-

the dramatic dematerialization of our cars, which means reducing material and energy inputs and waste; and

-

the democratization of car manufacturing, which means giving small teams a set of affordable tools that enable them to design, build, and scale a wide range of complex vehicle structures.

Dematerialization is the only effective path by which we reduce the environmental damages stemming from automobiles. Dematerialization will lead to far fewer emissions from both manufacturing and operation, much lower material and energy inputs in manufacture, dramatically better gas mileage, lower wear on roads, and fewer fatalities from car accidents.

Yet to dematerialize manufacturing, we first need to democratize it. Traditional auto-makers are held captive by the massive capital investments required to build cars using traditional methods. Every one of today’s car companies, from Toyota to Tesla, has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in every car factory it has built. That means they must organize everything they do around generating a maximum return on that huge fixed cost investment. As industry analyst Horace Dediu observes, “Production is everything. Capacity utilization is the first priority for an auto manufacturer. Capacity is why firms are not allowed to die and entrants are not allowed to enter. If you want to find the Next Big Thing in automobiles, look for a new production system.”[3]

Democratizing car manufacturing requires that small teams have a set of affordable tools that enable them to make cars of their own design. Such a tool set would empower people in car manufacture the same way ARDUINO empowered people in electronics. ARDUINO is a modular platform that hides its complexity behind an interface that is easy to use. It thereby enabled an explosion of hardware and software innovation. Because of ARDUINO, many of the latest tech products—from Kickstarter devices, to the Internet of things, to home automation—have been built not by huge corporations, but by small, nimble teams.

At Divergent Microfactories, we set out to build an industrial-strength ARDUINO for cars—a kind of CARDUINO, so to speak. The key enabling technology we’ve developed is what we call a Node. A Node is a 3D-printed alloy connector that joins aerospace-grade carbon fiber tubing into standardized building objects. This simple tool can enable a small team to design and build car chassis that range from two-seat sports cars to pick-up trucks. Just like with the ARDUINO, the Node hides its underlying complexity behind a simple, easy-to-use interface.

The Node-based chassis solves the bigger problems we set out to address. It drives dematerialization and democratization. A traditional chassis can weigh over 1,000 pounds, whereas we have built a prototype that weighs about 100 (61 pounds of aluminum and 41 pounds of carbon fiber), even as it’s much stronger and more durable. All of the nodes and carbon fiber tubing that make up a car chassis were fit into the backpack in the photo below. The chassis requires dramatically less material and energy to produce.

A dematerialized car is a greener, lighter, and safer car that can be made locally. It will have less wear on our roads and fewer fatalities in accidents. A super-lightweight car built with Divergent Microfactories’ new technology generates only a third of the total health and environmental damage of an 85 kWh all electric car. Our objective is drive that down to a quarter or less. And it can be made locally and built to last.

The chassis in this time-lapse video was assembled by hand in under half an hour (it could be assembled in about 15 minutes with a small robotic cell).

Whereas a traditional car factory would cost hundreds of millions of dollars, one of our micro-factories would have a startup cost of under 20 million dollars and produce up to 10,000 cars a year. If we centralize Node manufacture, we think it is possible to create microfactories that would cost less than $5 million to set up.

Just as the PC democratized the computer industry and ARDUINO democratized electronics, so our solution will give small teams all over the world the tools to develop and build innovative new car designs that will meet the needs of local communities. Now, because of Divergent Microfactories, you no longer have to be a billionaire to design and build new cars at scale. Imagine hundreds or even thousands of small teams around the world, bringing real innovation back to the car industry for the first time in nearly a hundred years through a network of pioneering teams. These teams would diverge and share, accelerating the pace of innovation, while protecting our environment—and then applying that knowledge to other complex structures.

The only sustainable path forward for the car industry is in dematerialization and the democratized innovation that will drive it. With the introduction of Divergent Microfactories’ tools, we believe that future is now possible.

Here is the first living example of what we can achieve: the world’s first 3D printed supercar. It has one-third the emissions of an electric car, one-fiftieth the factory capital cost, and twice the power-to-weight of a Bugatti Veyron.

[1] Emmott, Stephen, Ten Billion, p. 95, New York, New York: Random House, Second Edition, 2014.

[2] “Unclean at Any Speed,” Ozzie Zehner, IEEE Spectrum. June 30, 2013. http://spectrum.ieee.org/energy/renewables/unclean-at-any-speed

[3] “The Entrant’s Guide to The Automobile Industry,” Horace Dediu, Asymco. February 23, 2015. http://www.asymco.com/2015/02/23/the-entrants-guide-to-the-automobile-industry

Tom Burkart is the founder and managing editor of Car-Revs-Daily.com, an innovative and rapidly-expanding automotive news magazine.

He holds a Journalism JBA degree from the University of Wisconsin – Madison. Tom currently resides in Charleston, South Carolina with his two amazing dogs, Drake and Tank.

Mr. Burkart is available for all questions and concerns by email Tom(at)car-revs-daily.com.